Can Funny Pandemic Memes Help Get You Through COVID-19 Related Stress?

By the spring of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic had gripped the globe. Illness spread, lockdowns ensued, and both news outlets and medical journals documented the fear, anxiety, and subsequent stress everyone faced to one degree or another.

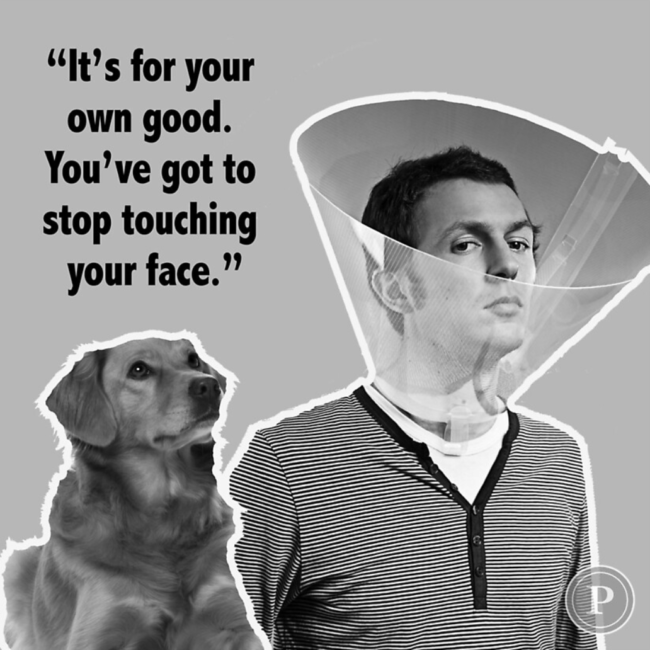

Like many people during this time, I was working from home and connecting with friends and family virtually instead of face-to-face. I was spending more time online—and on social media, in particular—when I started noticing people making memes specifically about pandemic experiences. These were satirical, highly visual takes on the difficulty of procuring toilet paper or the happiness of dogs who now had our constant companionship. They made me laugh.

But as a scholar who studies how media affects our emotions and well-being, they also made me think: why are these meme-based takes on the pandemic so popular? Are memes helping people deal with the pandemic in ways that may not be immediately obvious? To address these questions, I decided to collect some data.

But first, I asked two of my favorite colleagues, Dr. Robin Nabi at the University of California Santa Barbara, and Nicholas Eng, a doctoral student in our program at Penn State University, if they had noticed the same proliferation of meme-related content and if they felt any sort of comradery, relief, or stress-reduction from viewing it. They had. And so, the three of us decided to empirically study this potential phenomenon.

In December of 2020, we used CloudResearch to launch an online experiment on Amazon Mechanical Turk, a website that hosts online research studies. Our experiment involved showing participants different types of memes (or no memes at all) so that we could better understand if and how memes influenced people’s stress and ability to cope during the pandemic. Our paper was recently published in the journal Psychology of Popular Media.

What Is A Meme And Why Study It During The Pandemic?

Memes existed long before the internet, and although they continue to evolve, they are often defined as any form of popular cultural information. Sometimes meme images are re-used, the ubiquity of photo-editing websites and software makes it very easy for users to generate their own captions on popular meme images, like “distracted boyfriend,” “handshakes” or “Bernie’s mittens.” The fact that people can recognize the visuals in many social media memes, even when the captions are different, helps quickly connect them to others who are also in tune with Internet culture.

My colleagues and I wondered what, exactly, it is about memes that might help mitigate people’s stress levels during a very stressful time. Was it the positive emotion derived from viewing something funny or cute? Did it help if the meme poked fun at the pandemic, or would calling attention to the pandemic create additional stress that counteracts the effect of the meme? Finally, did the visual focus of the meme matter: Was it better to view a meme about babies or puppies than one about adults or other animals?

A Meme Research Study: Experiment to Assess Causality

To test our ideas, we searched the internet high and low for examples of memes in all these different categories (captions about COVID or not, featuring humans or animals, featuring younger or older creatures). Then, we set about testing whether memes affect people’s well-being, at least in the short run.

We initially thought about surveying social media users and seeing what they thought about memes, but the reality is that much of the research in my field suggests that people often misjudge how different types of media affect them.

So, we decided to run an experiment where different groups of participants were randomly assigned to see different types of memes. Each participant in the study saw three memes to ensure the results were not due to the unique qualities of any one meme and to present a more realistic social media experience (i.e., people typically do not look at only one post and then lock their phones). The only difference between participants was the content of the memes they saw, helping us establish that the memes (or lack of memes) are what shifted their perceived stress and perceived ability to cope with pandemic-related stressors.

Since we defined memes as user-generated, popular images with superimposed text like the ones often found on social media, the first step in our research process was finding memes that people had made online and that others generally thought of as funny and/or cute.

We first conducted a pre-test using CloudResearch. We created a repository of more than 100 actual memes and showed a series of them (randomly selected) to 120 participants. Then, we had our pre-test participants rate each meme for how funny, cute, and realistic (as in, would be typical of a meme found on social media) they perceived it to be. From there, we had a nice sample of realistic memes we could show our main study participants. We used a factorial design comparing people who saw captions discussing COVID-19 or not, people who saw memes featuring humans or animals, and people who saw memes featuring younger or older creatures, along with three control conditions where people saw alternate content that was not a meme (see the paper for more details).

It was important to us that our participants be Internet users given that we were studying an Internet-based phenomenon of user-generated memes about life during the pandemic. Additionally, due to COVID-19 risks, on-campus research has been significantly limited at our universities. So, it made a lot of sense to launch this study as an online experiment as opposed to a laboratory-based experiment.

However, compared to experiments that take place in a laboratory, we lose a little bit of control when we move our research online because I cannot quite as easily tell who exactly is participating or if they are multitasking while participating. When conducting online research, I need to try to ensure as much validity to the research as possible because of these factors that can introduce noise into the environment of an online experiment and potentially affect the results.

As such, we used CloudResearch’s data quality features, such as blocking participants with duplicate IP addresses or suspicious geocodes, as well as verifying the worker’s country location since our IRB only allows participants who are based in the United States. We also used CloudResearch’s pool of approved participants to help ensure data quality. Because we had so many experimental conditions, it was very helpful to be able to quickly collect high-quality data from nearly 800 participants, all from the comfort of my living room couch with my two pug dogs sitting on my lap snoring, totally uninterested in all of my hard work.

A Meme A Day Keeps The Stress Away

What did our CloudResearch experiment find? Well, participants who viewed memes (any type of meme) rated themselves on a 1-7 scale as more content, amused, and calmer (average of 4.71) compared with participants who did not see any memes (average of 3.85). That is, viewing three cute or funny memes provided a quick boost of positive emotion for many people.

We also discovered that participants who rated themselves higher on the positive emotion scale felt more confident in their ability to handle the stress of the pandemic. Our data suggested that there is value in reframing stressful circumstances into a more approachable topic by using humor, cuteness, or some combination thereof.

Importantly, the topic of the memes also mattered. Participants who viewed memes specifically about COVID-19 rated themselves as less stressed about the pandemic. And, participants who saw COVID-19-related memes processed the information in the meme more deeply, with deeper information processing also related to higher confidence in their abilities to handle pandemic-related stress.

As for our other experimental factors, people found animals cuter than humans, and they found younger creatures cuter than older ones. Otherwise, there was not much difference on our primary outcomes of perceived stress and ability to cope with that stress.

Implications

Our research has a number of intriguing implications. First, while spending time online is often framed as “a waste of time,” we hope these results can encourage people to think about what they are doing online and how they are feeling when they are doing it. For example, if you find yourself turning to the internet mindlessly (i.e., without an a priori reason to use it), maybe think instead about what content would help you achieve your goals in that moment, and then seek out that content. As for me, if I find myself scrolling and not able to remember why I picked up my phone in the first place, then I realize I typically need to take another quick look at my to-do list for the day and decide if I have more time for aimless scrolling or if I would rather take a quick walk or get back to work.

Moreover, noticing our patterns of media use and how they may cooccur with certain emotional states can give us greater insights into the role of media use in our lives. If you notice that you often turn to the Internet and social media when you are stressed, for instance, then consider seeking out a fun meme account and looking at that for a few minutes before returning to tackle your goals. This, based on our meme study, may help lessen your stress levels whereas other forms of social media that cause you to compare yourself to others or that introduce distressing news, may not be ideal to view during those times when you know you are stressed.

Another implication of this research is that we could pair content like memes with the more distressing media content that is still important for us to consume as global citizens. Although the news can be distressing, it is also important to stay up to date on current events and to be informed of ways to address society’s challenges. So, what if we first viewed a few memes about current events and then read the news? That may be a way to both cope with the stressors of the modern world while remaining engaged with it.

A big caveat when discussing any of these ideas: We were studying dogs wearing glasses and screenshots from movies about pizza; and, therefore, we were not studying memes with embedded factual content or misinformation. As such, there is the chance that with their popularity and emotional benefits, memes could also be a force for concern, quickly spreading false information to millions of people, or reinforcing false beliefs people already hold.

While it is only one study, we hope future work takes advantage of the tools available to researchers to conduct online experiments and builds on the potential of viewing memes to help us cope with stressful situations. And if you find yourself stressed, please, just take a quick break, look at some memes (if you’re like me, they should definitely include dogs), and then proceed.